After years of resisting widespread calls to release prisoners of conscience in Saudi Arabia, the authorities began, in late 2024, to release dozens of such individuals from prison. This development raised many questions among observers, human rights organisations, journalists and others, as the motives behind these releases were far from clear. Nor can they be understood as serious or genuine steps towards reform.

In many cases those released had already completed their prison sentences, and in some instances exceeded them, before being freed. One prominent example is Mohammed Fahad al-Qahtani, a founding member of the Saudi Civil and Political Rights Association (ACPRA), who served his full prison term and, instead of being released, was subjected to enforced disappearance for a prolonged period before his eventual release after several additional years in detention. In other cases, prisoners completed an initial sentence only to be tried and convicted a second time, served that additional sentence in full, and were then released months or even years after its expiry, as in the case of Essa al-Nukheifi. In yet other instances, excessively harsh sentences were partially reduced following intense international pressure, most notably in the case of Salma al-Shehab. Arrested in 2021 for feminist tweets supporting Saudi women’s rights defenders, al-Shehab was initially sentenced to six years in prison, a term that was later increased to an extraordinary 34 years. The sentence provoked global outrage and sustained advocacy campaigns, eventually leading to a reduction of her sentence and her release in 2025.

In several cases, individuals were reportedly informed of their release on a personal basis, without any official announcement of a royal pardon. Notably, King Salman did not issue a comprehensive or public royal pardon for all prisoners of conscience at the outset of his reign, unlike previous Saudi monarchs.

In other cases, no explanation was provided at all: no pardon was announced, no sentences were formally quashed, and no legal justification for the releases was offered. Nevertheless, some observations can be made about the likely reasoning behind this apparent policy shift, if it can indeed be described as such.

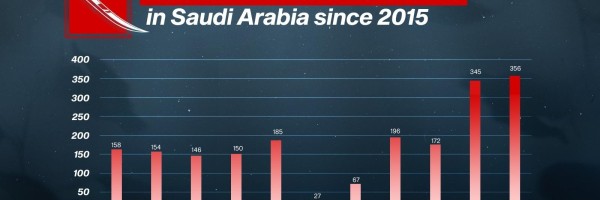

As advocacy efforts by organisations such as ALQST and other human rights groups, alongside UN mechanisms, have intensified, the public relations cost of detaining large numbers of political prisoners and peaceful social media users has become increasingly evident to the Saudi authorities. This has coincided with the kingdom’s ambition to position itself as a global hub for economic, sporting and entertainment events. Human rights pressure has accompanied nearly all of these initiatives. Rather than allowing these events to function as vehicles for “sportswashing”, “entertainment-washing”, or “economic-washing”, organisations such as ALQST have used them as platforms to spotlight ongoing human rights violations.

In many cases, the sentences imposed on prisoners of conscience were not only unjust but extreme even by the standards of an authoritarian system. The case of Salma al-Shehab remains one of the clearest illustrations of this dynamic.

Looking ahead, preparations for hosting the 2034 FIFA Men’s World Cup in Saudi Arabia, along with the many other international events the country currently hosts, are expected to place the kingdom’s human rights record under unprecedented scrutiny. This mounting pressure may have prompted the authorities to release a limited number of prisoners while continuing to impose severe restrictions on them. These include travel bans, denial of employment opportunities, house arrest for some, suspension of government and financial services, and, in certain cases, long prison sentences that remain formally in place but are not currently enforced. As a result, many released individuals continue to live under conditions that closely resemble detention, despite their formal release.

The authorities’ selection of which prisoners of conscience to release also sheds light on their rationale. The majority of those released had already finished their sentences or were arrested from 2018 onwards. Meanwhile, many veteran human rights defenders remain behind bars and are expected to serve many more years of unjust imprisonment. These include ACPRA members Issa al-Hamid, Mohammed al-Bejadi, and Omar al-Saeed; Jeddah reformist Saud al-Hashemi; and Waleed Abu al-Khair, Khaled al-Omair, and Mohamed al-Otaibi.

It is crucial to stress that the release of prisoners of conscience at the end of lengthy prison terms is not a concession by the authorities; it is a basic right. Moreover, nearly all those released remain subject to extremely restrictive conditions that severely limit their freedom of movement, employment and communication. Those who were subjected to grave abuses including torture, sexual harassment, enforced disappearance and arbitrary detention (which applies to all prisoners of conscience), have received no apology, no compensation, and no justice. None of those responsible for these violations have been held accountable.

Finally, the authorities may believe that these ambiguous and oppressive post-release conditions, and the fear they generate, are sufficient to ensure silence. They may also calculate that keeping many activists imprisoned under unjust sentences, while releasing others under strict travel bans, employment restrictions, social media controls and electronic surveillance, will reduce international pressure and advocacy campaigns.

It is therefore essential to be clear: human rights violations in Saudi Arabia have not ended. While the release of some prisoners is welcome and a source of relief, the continued detention of many others, alongside the severe restrictions imposed on those released, demonstrates that repression persists, albeit in different forms. This reality underscores the urgent need for sustained and ongoing human rights advocacy.